A fistful of MASE: Deconstructing DeepAR

1. Introduction

Hey Amigos! Four years since its release, DeepAR is an old timer in the world of neural networks for time series forecasting, but it can still outshoot many of the young guns out there and remains a popular choice to benchmark against. But like many gunslingers, it can be elusive and hard to pin down what makes it tick. In this post, we're gonna get our hands dirty and deconstruct DeepAR to understand what really drives its performance. In particular we're going to use the Pytorch GluonTS implementation as our reference. So saddle up and let's get rolling.

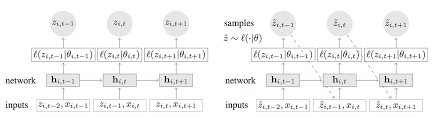

DeepAR Encoder-Decoder Architecture [source](https://arxiv.org/pdf/1704.04110)

The model is described as having an encoder-decoder architecture, which at first glance can make it seem more complex than it really is. Typically, an encoder-decoder architecture takes some high dimensional input and compresses it into a lower dimensional "latent" representation and the decoder then takes this latent representation and generates a high dimensional output. There are a number of advantages to this, but one is that it allows the encoder and the decoder to have different architectures. In the case of DeepAR the encoder and the decoder are the same architecture, and not only that but they share the same weights. There seems to be a family resemblance, but they are not brother and sister, they are the same person, mathematically equivalent. The encoder and decoder are described separately probably to make it easier to understand the concepts in the paper. Once we take this into account, and if we ignore the output layer, what we're left with is basically a bog-standard vanilla LSTM.

Plot of the month feature

This is because January is month 1 and December is month 12. This means that we are telling the model that the months that are most dissimilar are January and December which in reality is not the case. A better approach would be to use something like the positional encoding schemes used in transformers which use a sine and cosine function to encode the position of the timestep with the wavelength set to the seasonality (ie 12 for monthly time series). This would give us a continuous representation where adjacent timesteps are more similar than distant timesteps.

Lastly we have a "scale" feature, which simply takes the log of the scale value calculated with the mean absolute scaling. I'm not entirely sure why this works, but my perception from using this on the base-lstm model from my last post, is that it does indeed help the model pick up the trend of the data more accurately. However I have no empirical proof of this in DeepAR so we're gonna test that now.

So, my hypothesis is that none of these features in their current form actually help the model to make better forecasts. I'm going to test this by performing what's called an ablation study. This means that we will train several models with different combinations of features and then compare the results. We train each model 5 times with different seeds and then calculate the average of the metrics for the tourism dataset and the electricity dataset. Now to be clear, we are going to use my implementation of DeepAR), which is not the same as the GluonTS implementation. My implementation produces point forecasts and is therefore trained as a regression task. Yes I know that DeepAR is a probabilistic model, but for the purposes of finding out which features are making a difference, I think we can safely ignore this. Apart from this the model architecture and the dataset are the same.

Electricity MASE

Tourism MASE

If you're interested you can find more details on these WandB projects Electricity} and Tourism, but to me with Electricity it looks like there maybe some suggestion that using few features is better than using many, but not statistically significant. The tourism results are all within the same standard error. My conclusion overall is that these features either individually or collectively do not help the model to make better forecasts.

So if we're using a vanilla lstm and these covariates are not helping, what is it that makes DeepAR so good? Well, partner take a seat by the campfire and I'll tell you.

When you create an estimator in GluonTS you can specify a lag sequence. This is a sequence of historical timesteps that will be added to each timestep as covariates. If we specify a lag sequence of 12, then alongside our input data we will also include the data from 12 timesteps ago ( or a year ago in the case of a monthly dataset like Tourism). If you don't specify a lag sequence, then GluonTS will create one for you based on the frequency of the data. For a monthly dataset like Tourism the default lags are:

[1, 2, 3, 4, 5, 6, 7, 11, 12, 13, 23, 24, 25, 35, 36, 37]Lag sequence for monthly dataset

For an hourly dataset like electricity the lag sequence contains 40 lags between 1 hour and 721. Now if you're there thinking, isn't it a bit odd that we're using covariate features that contain temporal information from the past in a model whose architecture is designed to capture temporal information from the past, then you're not alone. What impact do these lags have on performance, well let's test it and find out. As before we're going to train models with different lag sequences and compare the results. We'll start off with 1 lag and gradually add more and more.

Tourism Lags MASE

What do you think of that? The more lags we add the better the model performs. My boy, you've become rich. It seems we've found the secret sauce that makes DeepAR so good.

5. Conclusion

One of the key issues that I think we have with the benchmarking of these models is the size of the context length or the look back window. This is how many timesteps the model can see in the past when we use recurrence. For Tourism it's 15 and Electricity it's 30. Let's just put that into perspective, we're going to provide a day and a quarter of data to a model and expect it to forecast the next 7 days. Now I'm not saying that if the context lengths included the same time range as the lags that we could exclude the lags and still get the same performance but I do think that this configuration does not allow the lstm to do what it does best.

Overall, despite my misgivings about the covariates and some of the implementation details, DeepAR is a very powerful model that can outperform even the latest generation of transformer based models and maybe there are some areas where it can be improved further still.

So there you have it, a look at what makes DeepAR tick and this is where we part ways, so long, adios amigos.