NeurIPs Ariel Challenge: What's it like to take part in a Kaggle competition?

Introduction

I've spoken about Jeremy Howard many times before, but of all the things that he has opened my eyes to Kaggle, the popular data science competition platform, is the one thing that until recently I haven't properly invested time in. However as part of my quest to demonstrate that I at least possess a modicom of competence in the field of machine learning and AI I decided to change that when I took part in the recent Neurips Ariel Challenge competition. In this post I'm going to talk about my experience of taking part in a competition on Kaggle and what I learned from it.

What is Kaggle?

For the unitiated Kaggle is a platform that hosts data science competitions. The idea is that companies or organisations can post a problem that they have in the real world, along with a dataset and invite the community of 'Kagglers' to come up a solution. The better the solution the higher your score and the more likely you are to win a prize. Typically competitions are run over a period of a few months and solutions are submitted in the form of Jupyter notebooks which execute python code run on Kaggle's servers. Now the competitions themselves are varied, as of the time of writing you can take part in competitions for Google Gemini, mathematical reasoning, financial forecasting and American Football tactics. The chances are that there will be something that will interest you. Competitions on Kaggle tend to follow a similar format. The organisers of the competition will provide a training dataset and define a metric that they will use to evaluate how well a model performs. The metric is evaluated on a test set of the data that is not available to competitors. The idea is that you write code in a notebook that will do all the work required to load the data, process it, define and train a model and finally generate predictions. Once your notebook is complete you submit it to Kaggle and your model is then scored on the test set and your score is displayed on the leaderboard. This gives you an idea of how well your model is performing, but this test set is not the final test set, oh no if only life were that simple. The test set that is used for the leaderboard throughout the competition is only a subset of the final test set that will be used at the end of the competition to make the final results.

The Ariel Challenge

For me, I really wanted to get stuck into a problem that was new, to take a busman's holiday from my usual break and butter. I've had a modest interest in Astronomy for a while, by which I mean the kids and I have taken a small telescope out into the back garden and we've looked at Jupiter. So when I saw the astronomy based Ariel Challenge, to support the Ariel space telescope I thought it would be a great opportunity to learn something new and potentially contribute to something worthwhile.

Another reason why it caught my attention was that it formed part of the NeurIPS competition track. NeurIPS along with ICLR and ICML is the most presigious conference in the field of machine learning and AI. As such I figured the competition would have good participation with some of the best minds in the field taking part. I wasn't wrong as it attracted well over a 1000 participants.

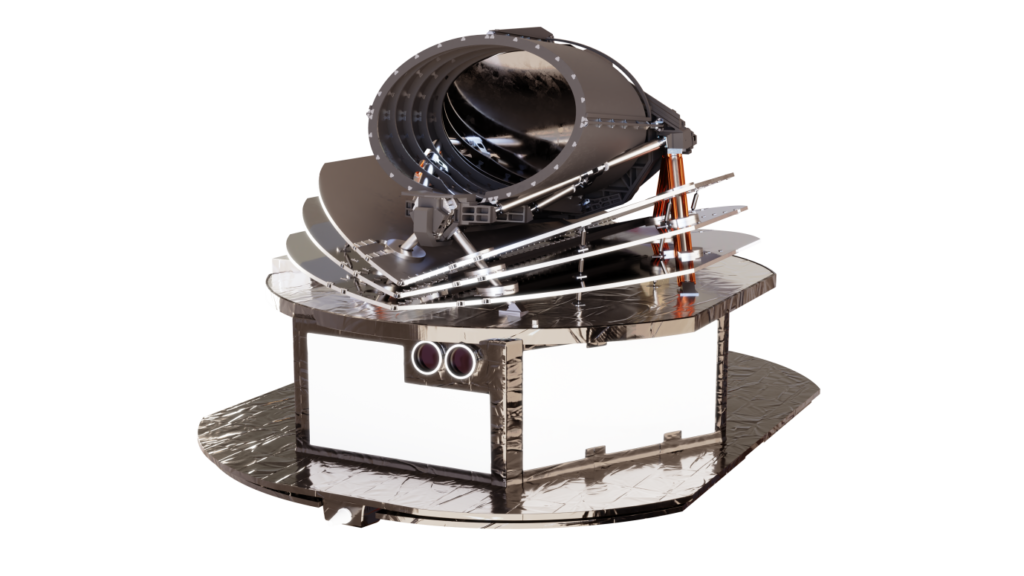

So the idea is this. The Ariel space telescope is going to be launched in few years and its mission is to detect exoplanets, that is to say planets that are outside of our own solar system. The way it does this is by looking at stars and detecting the drop in the light that occurs when a planet passes in front of it and blocks out some of the star light. Typically the reduction in light is very small so that is difficult enough to measure, but hold on because things are about to get a whole lot more crazy. It turns out that it's possible to detect the light that passes through the atmosphere of the planet as it passes in front of its star, and that light can tell us a lot about what's in the atmosphere. Certain molecules will absorb certain wavelengths of light and so by looking at the spectrum of light that passes through the atmosphere we can infer what molecules are present and hence what the atmosphere is made of. Now as you might imagine pointing a telescope at a star that is millions of light years away and trying to detect the light as it passes through the tiny slither of the planet's atmosphere is no mean feat, and the organisers expect to be able to gather only a tiny handful of photons in each case, and so even in space, where nobody can hear you scream, the machinery of the telescope itself, the sensitivity of the detectors and a whole host of other factors will generate noise that will drown out the signal. And so the challenge is to build a model that can infer the true atmospheric spectra of the planet from a long sequence of noisy images that are obtained as the planet "transits" its star. Now the observant amongst you may have cottoned on to the fact that half built space telescopes sitting in a laboratory tend not to produce brilliant vistas of the milky way, and so the organisers provided simulated data for us to work with, which I must admit I wasn't sure about at first, but in the end I don't think it was a bad thing.

Artists impression of the satellite

In most competitions you can make 5 submissions a day, but in this one it was 3 which added another dimension to the challenge, as you had to be much more careful about how you used your allocation of submissions. Each submission had to include the prediction and uncertainty for 283 wavelengths for each exoplanet example. The metrics that was used to evaluate peformance was essentially a scaled measure of likelihood from a gaussian distribution. So we have to try and produce a model that will minimise uncertainty and maximise the accuracy of the prediction.

So in a nutshell we are provided with a series of images from the telescope as a planet passes in front of a star, from which we have to predict true undelying spectra of 283 wavelengths along with our uncertainty of each prediction of light which is a function of both how much light is blocked out by the planet and the atmosphere of the planet.

Getting Started

OK so we understand the nature of the problem, the format of the competition and have acccess to some data, but how do we actually get going? The nature of how we are wired to tackle complex problems I think is a fascinating one in its own right and is the main subject of this post.

My natural inclination is to get something working as quickly as possible. I don't particularly care if there are huge gaps in my understanding as I will aim to fill those in as I go along, but unless I can see and follow code executing I struggle to get a handle on the essence of the problem. So first objective was to submit a solution, any solution and get a score that I can then improve upon.

With no real domain knowledge this is a daunting and perhaps foolhardy prospect, but fortunately, help was at hand in the form of discussion forums for the competition. Competitors and organisers can post information, share ideas (within reason) and ask questions, and for most part this is a pretty friendly place. The organisers had very helpfully prepared a notebook that was a possible solution ( a sort of baseline starter), so to me this was the obvious place to start.

The Baseline

Conceptually, the organiser's solution was fairly straightforward, but there was an awful lot going on. Firstly, the data processing was pretty complicated as there was an a lot that needed to be done to calibrate and clean up the signal. Once the data was processed, there were two models: one to predict the transit depth ( how much light the planet blocks out) and another to predict the spectrum of wavelengths. Both models were CNN's and so this is pretty familiar territory for me, so I just ported the code into pytorch ran it and then submitted it for scoring. The higher the score the better: a perfect score would be 1.0 and the leaderboard at the time was topped by someone with a score of 0.6. After two hours of waiting the score came back as ... drum roll please... 0. Zero, nothing, nil point, not a sausage. This couldn't be right I told myself, there must be a mistake in the code, but no having checked all the details my validation set score was 0.6 and my errors were being measured in a few parts per million. Everything checked out fine but zero was the score. WTF.

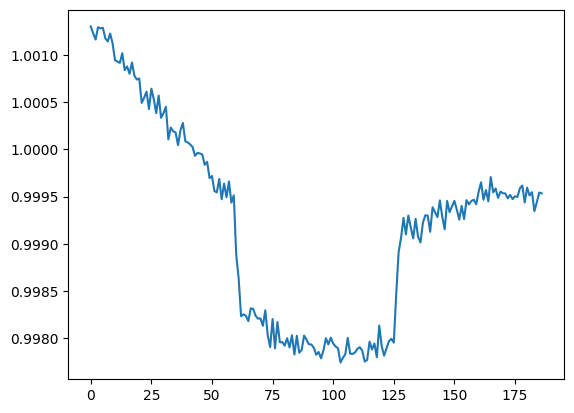

And so here we arrive at the crux of this challenge. The data that's in the training set is not the same as the data in the test set. No matter how well my model performed in training or how I split the training set, when it came to submissions, the scores I got were all the same. Moreover if the baseline solution provided by the organisers came back as zero, then how on earth was anyone else going to come up with a better solution? So I started trawling the discussion forums and eventually found sanctuary in a thread which proposed a solution that esimtated the transit depth with a genius solution that had no hint of a neural network. The idea was this: Fit a line to the light when the planet is not in transit, and then take the line when the planet is in transit and "lift" it up to fit the line and measure how much the line has been lifted. Apart from a simple 2d linear regression in numpy there was no machine learning at all. It's the simplicity of the approach that I think is most impressive and sure enough I get a score that's not zero... first objective achieved.

Estimating the transit depth

The Learning Curve

Let me say that challenges like this tend to suck me in.

There was a fascinating Lex Fridman podcast with Andrej Karpathy a while back where they were discussing a productive day. Andrej was describing how he would spend time thinking about a problem, mentally absorbing as much information as he could in order to think, almost obsessively, for a limited period of time.

You need to build some momentum on a problem. Without too much distration, and you need to load your RAM, your working memory with that problem. And then you need to be obsessed with it, when you take a shower, when you're falling asleep... and it's fully in your memory and you're ready to wake up and work on it right there.

For me that's an uncomfortably familiar trait, but as I slowly start to make sense of the problem I can't help thinking about similar problems and solutions I have read about or seen work in the past. There's a time element to it ... well obviously we need to look at a timeseries model. Noisy data you say... no problem let's try a denoising autoencoder. Uncertainty quantification... well let's use a gaussian probabilistic head. Limited training data? Easy let's do some data augmentation and generate synthetic data. And the problem is that I start to build up a mental image of what the final solution is going to look like long before I've obtained any evidence to suggest that it's going to work, and in a time limited competition like this that is a dangerous thing. Honestly I spent an entire week trying to make a denoising diffuser work in latent space ( you know like stable diffusion ) because I was convinced it was the holy grail and was going to propel me to the top of the leaderboard. Inevitably, it wasn't and I eventually had to admit that to myself and move on to the next idea.

Now I'm not saying that trying out new ideas is a bad thing, obvisouly it isn't, but picking and choosing which ideas to try and how long to invest in each one is something which can be difficult to get right and in a time limited task like this it really matters. Interestingly I found that it was my understanding of the domain and the data that I picked up along the way that really made a positive difference. For example one day I was investigating training examples that were performing really poorly with the baseline model, and plotted the light curves of the training examples against the target spectra that we were trying to predict and I noticed that the light curve was the mirror image of the target spectrum. If I flipped the light curve I got a much better match and sure enough it turned out that the images from the raw data were indeed arranged in the reverse direction on the wavelength axis and needed to be flipped to get them in the same order as the target labels. (something to do with the spectrometer being installed the wrong way around).. just quite how that works on a space telescope that hasn't been launched yet I'm not sure. Now you could argue that the organisers should have provided this information, but I'm not sure that they were aware of this themselves, which just goes to show that sometimes just sitting down and eyeballing the data can be more effective than any fancy model.

Noisy images combining in time and the target spectra

But here's the thing and the point I'm trying to get to, I like to think that there is a fundamental truth to the data and much of what we want to do is extract that in the most transparent way possible. At the end of the day this was a task of regression, given a set of input images find a function that maps them to a set of output spectra. The further we move our attention away from the underlying characteristics of the data the less likely we are to find a solution that works. I'm not just talking about eda and feature engineering, but also the underlying physics of the problem. For example the amount of light that a planet blocks out is a function of the radius of the planet, the radius of the star and how far the planet is from the star. We know this is going to be in a range of 0.1 - 1% and so if we're getting values that are outside of that range then we know something is wrong. We know that there are only a finite number of molecules in our universe each of which will absorb light at certain wavelengths so we should be able to figure out some features of the spectra that we are trying to predict. The best competitors used made use of all this information and more.

As far as this competition was concerned I think I spent too much time on things that didn't really tackle the issue at hand. Even going into the last week I was trying to make sense of the test set. Maybe the origanisers had made a mistake and I should flip the wavelengths on the target values I thought to myself. Maybe I should try and model the characteristics of the test set from my submission scores. Ideas which in hindsight were a waste of time, but seemed absolutely essential at the time.

The majority of my progress came during the last week when I really started to simplify my approach and focus on the fundamentals of the problem. At the end of the day a simple model which decomposed the signal into moving average components and a simple model that I will descibe in another post was my best performing model.

Conclusion

I have to say that the time and dedication that some of the competitors put into this competition was truly impressive. Whilst it is ultimately rewarding and I think we can all feel a sense of accomplishment, it's mentally exhausting and so when I finally got to see the work from the top competitors after the competition had finished I can only admire their dedication and skill and if they feel anything like me then they will be in desparate need of an intellectual break.

Now I really don't want this to sound like some preachy know it all from your favourite social network stating the bleeding obvious, but I guess I need to try and draw some conclusions from this experience. So what did I learn?

- Fail fast and quickly move on to the next idea

- Focus on the fundamentals of the problem and do not deviate from the task at hand

- Understand the data and the domain

- Make no assumptions about what will work.

- Think laterally and always go for the simpler option.

At the end of the day my efforts were rewarded with a bronze medal ( which are awarded to competitors finishing in the top 10% of the leaderboard), I know a little bit more about exoplanets than I did before and have some some sense of how to get the most out of a competition like this.

I mentioned Andrej Karpathy earlier and a podcast that he gave. There's a great section in it where he talks about advice that he would give to beginners interested in getting into machine learning:

Beginners are often focused on what to do and I think the focus should be on how much you do.. .. you'll iterate, you'll improve, you'll waste some time. I don't know if there's a better way. You can literally pick an arbitrary thing, and I think if you spend 10,000 hours of deliberate effort and work you actually will become an expert at it.

As far as Kaggle competitions go I think I and many others have made a significant dent in that 10,000 hours and maybe that investment is the most valuable thing that we can take away from it. Overall I would say that this was a positive experience and a great way to very quickly learn techniques and approaches that you are not familiar with. It's not for the faint hearted, but as with many things I think you get out of it what you put in.