Multivariate Time Series models: Do we really need them?

In my last post we took a dive into the 2022 paper, Are Transformers Effective for Time Series Forecasting and looked at how the DLinear and NLinear models that it introduces perform in both multivariate and univariate settings. Whilst doing the experiments and analysis I noticed some interesting things happening, like why it would sometimes take hours to train in a univariate mode, but only a few seconds in a multivariate mode. So I thought I would take a closer look and this led me on a journey to where I now question the whole premise of using multivariate models at all. For those of you who are interested, in this post I'll share my observations and conclusions.

All the code for this post can be found on my nnts github repo.

Recap

So just to recap, in my previous post we implemented the embarrassingly simple LTSF-Linear models: DLinear and NLinear named as such because they are single layer linear models developed to prove a point that you don't need a transformer to get state of the art performance on multivariate long term forecasting problems. We learned that the models could also emulate a univariate model by setting a parameter named "individual" in the model. This parameter modifies the model architecture so that each time-series in the dataset we are training has its own dedicated mini linear layer that projects the lookback window onto the required forecasting space. We also learned that this configuration was tested in the paper using just one time series, "OT" from the ETT dataset and I claimed that in this configuration the model was not a global model but a local model. So I was interested in a few things which I'll introduce here. Don't worry if it's confusing, I'll explain everything in more detail later.

- Can we create a comparable univariate global model to the multivariate model?

- Can we test the performance of the models in the "individual" configuration on a dataset containing multiple time series?

- Is my claim that when trained on one time-series the "individual" model is a local model correct?

- How does the performance of the models compare in different configurations?

So with that in mind I want to make sure that we are all on the same page with the terminology that I'm bandying about here, so let's start with a few definitions.

Univariate Models

Most time-series forecasting datasets will comprise a single file containing multiple time series. For example the Tourism Monthly dataset has 366 individual time series, one for each region in Australia, New Zealand and Hong Kong. Each time series is a sequence of monthly observations and the number of observations in each series may be different as the historical data may start at different times in each region. When we forecast we aim to predict the future values for each of the time series across a forecast horizon, but because the time series in the dataset do not share a common time span we do not attempt to model the relationships between each time series, so we forecast each time series independently of the others. This is what we refer to as Univariate. Our input is a single time series and our output is a single time series.

Multivariate Models

In contrast Multivariate forecasting is where we have multiple time series that do share a common time span and we aim to model the association between the time series. This means that the input to the model is essentially a table of values containing a sequence of historical values for each time series in the dataset. Obviously this requires the dataset to be structured in such a way that all the time series are aligned and typical examples of this are ETTh, Electricity and Traffic datasets. In summary not all datasets are suitable for multivariate forecasting, but all datasets are suitable for univariate forecasting. Multivariate models are designed to exploit any correlation (or perhaps more correctly association) that one time-series has with another. Examples of Multivariate models are Informer, Autoformer, TSMixer and of course the DLinear and NLinear models.

Figure 1: Multivariate forecasting - a window of time from all the time series in the dataset is input into the multivariate model so that the model can uncover any relationship between each time series to improve its forecast

Local Models

Local forecasting is where we create a model for just one time series. So in our Tourism Monthly example we would create 366 individual models (one for each region) and then forecast the future values for each region independently. This is a perfectly reasonable approach but has some limitations, for example if we obtain a new time series for a new region we would have to train a new model and secondly as the number of time series increases the number of models we have to train increases linearly. Depending on the use case we may have tens or hundreds of thousands of model artefacts to manage. Local models are the norm in statistical forecasting examples being ETS and ARIMA.

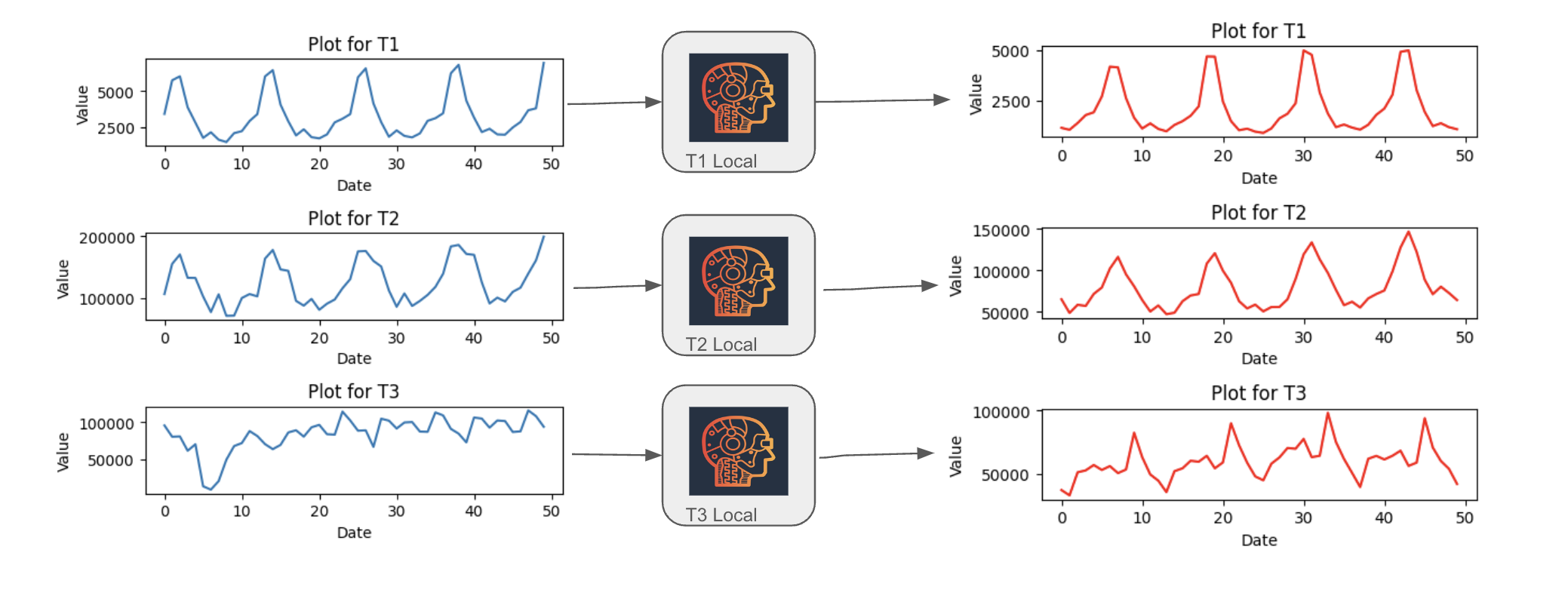

Figure 2: Local forecasting - a model is created for each time series in the dataset and the future values are forecast independently

Global Models

Global forecasting attempted to address the limitations of local models, by creating a single model that can forecast all the time series in the dataset. In this setting we train a model on a dataset containing multiple time series using samples from all the time series, but where each individual training sample contains observations from only one time series. Consequently, we only need to train one model and that model serves all the time series in the dataset, so effectively its parameters are shared between all the time series. This is more scalable than local models and most if not all neural network univariate models are global models. Univariate examples include N-HITS, N-BEATS and DeepAR.

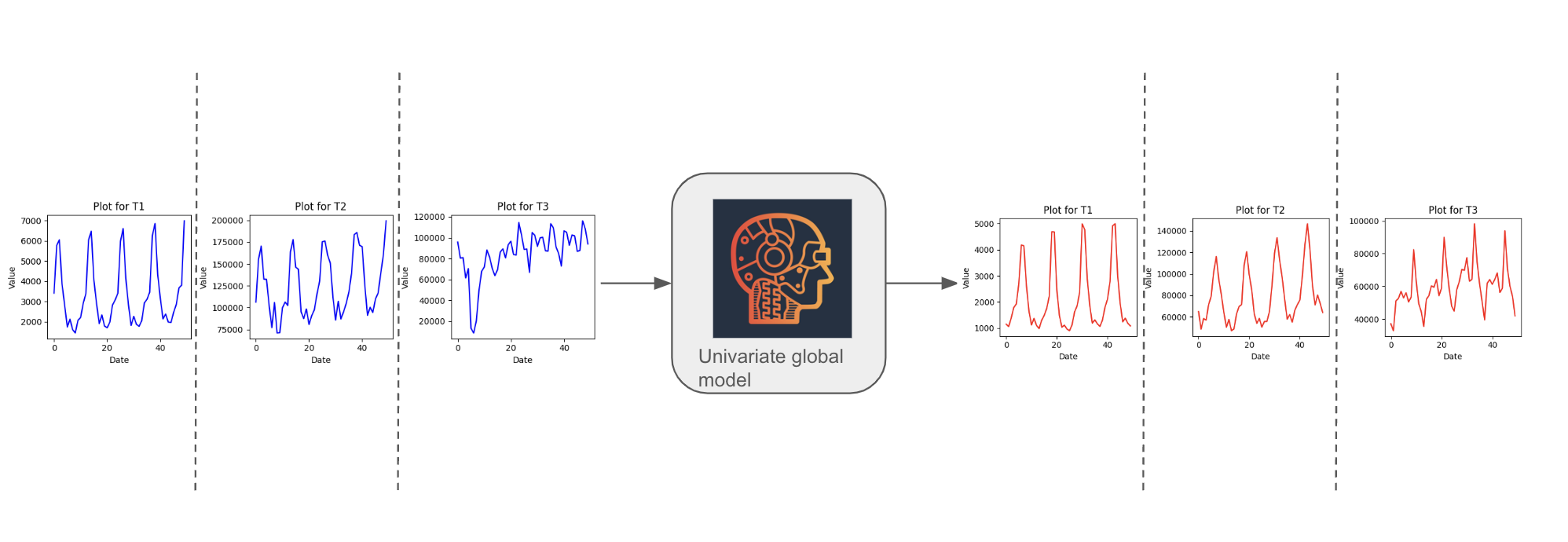

Figure 3: Global forecasting - a single model is created for all the time series in the dataset and the future values are forecast independently

The problem with the individual

So let's put the multivariate configuration to one side for a moment, because the real issue I was seeing was with the univariate (individual) configuration where I was seeing that it was taking orders of magnitude longer to train in some datasets than the multivariate configuration and in fact the problem got so bad that on datasets like Kaggle Web Traffic that I ended up killing the training process because after several hours it still hadn't completed one epoch.

In the individual mode a set of fully connected linear layers are created for each time series in the dataset. So each time series is "routed" through its own linear layer and as such the weights of these layers are dedicated to one time series as illustrated in Figure 4. To all intents and purposes this is a local model. However, everything else about the model is global. We sample all the time series in each training example, we calculate the loss across all the time series and we update the weights of the model based on the loss. In this univariate setting the model has a bit of an identity crisis.

Figure 4: Individual forecasting - a single model is created for a dataset but each time-series is handled in isolation being routed through its own dedicated fully connected layers.

The problem seemed to be related to the number of time-series in the dataset. The more time-series there were the longer the training. The ETT dataset that is very much the standard baseline to go to on multivariate forecasting research has only 7 time series, but Kaggle Web Traffic on the other hand has 145,063 time series. Initially I thought the issue was related to the number of parameters which is specific to each dataset, but when I saw that the multivariate configuration was training in seconds with the same number of parameters I realised that the issue was related to the number of matrix calculations that needed to be performed. You see in this channel individual configuration we no longer have one big matrix calculation for all the time-series as would be the case in the multivariate setting, but instead we have lots of little matrix calculations (two for each time-series in the dataset). Now that may not be an issue if there are a few hundred time-series, but when there are tens or hundreds of thousands performance just grinds down to a crawl. At scale this approach just does not work.

So, you may be asking yourself why wasn't this picked up by the authors of the paper? Well part of the reason I suspect is down to the experimental setup and the interpretation of univariate that was used which I will now describe. The univariate experiments in the paper were conducted using the ETT dataset, which has 7 time series, and followed the same methodology as many of the transformer papers which came before it and many since. From the ETT dataset one time series named "OT" is selected and all the other 6 time series are discarded. This makes it convenient to use since we only need to specify one channel, (ie we input one time series and the output is one time series), but the problem is that this is not a global configuration. The model is essentially a local one since we are only training it on a single time-series, and in my book that does not make for a fair comparison since a global model has to learn multiple time series at the same time.

Global, Local, Individual and Multivariate experiments

So you may be asking yourself why does any of this matter? Who cares if this is a local or a global model. Well it matters because when we use these models as benchmarks we need to ensure that we are comparing like for like. So in order to do this I have run the DLinear and NLinear models in the following configurations:

- Local - One model for each time series. Essentially I trained multiple models (one for each time-series) and evaluated each of them. Since the metrics I present are first averaged for each time-series we can compare these results directly.

- Individual - So just setting the individual flag to true and training the model on the dataset. This is what we believe has an identity crisis with having an architecture that behaves locally, but data sampling and optimisation that is global.

- Multivariate - One model for all time series forecasting all time series simultaneously. This is the default configuration used in the paper.

- Global - One model for all time series forecasting each time series independently (To achieve this the models were set to have one channel and then trained using a univariate data sampling strategy)

The datasets that we'll be using are from the Monash repository which I've used in previous posts. The forecast horizons are diverse and come from different domains. For brevity I'll just present the results from 6 datasets.

Computational Efficiency

The first thing we'll look at is the computational efficiency of the models. Table 1 below shows the total training time in seconds for 100 epochs for each configuration.

| Model | Local | Individual | Multivariate | Global |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Car Parts | 446.966 | 124.398 | 6.175 | 11.325 |

| COVID | 203.772 | 32.353 | 8.806 | 8.735 |

| Electricity Hourly | 2521.712 | 1685.107 | 240.695 | 11.053 |

| Electricity Weekly | 137.398 | 23.509 | 5.501 | 9.339 |

| Traffic Hourly | 7098.796 | 13801.659 | 462.455 | 12.987 |

| Traffic Weekly | 214.614 | 29.594 | 5.048 | 9.484 |

Table 1 DLinear model total train time in seconds for 100 epochs. Shortest training times are shown in bold

As we can see the global and multivariate configurations train far more quickly than our local configuration or the channel individual setting. In the extreme case the Traffic Hourly dataset takes 3 hours 10 minutes to train with channel individual, but just 12 seconds in the global configuration. Local model configuration is usually the slowest, which I think is to be expected since the sampling and optimisation is done separately for each time series in the dataset.

The fact that there is such a marked difference between Individual and Multivariate proves that performance is dominated by the number of separate matrix calculations that need to be performed and not by the total number of trainable parameters.

Forecast Accuracy

So now let's turn our attention to how well each configuration performs in terms of forecasting accuracy. Maybe the performance of the local and independent models are so good that they justify the extra computational cost. Table 2 shows the result of the Mean Absolute Scaled Error (MASE) for each configuration on the 6 datasets. The best error for each data set is shown in bold and the second best in underlined.

| Model | Local | Individual | Multivariate | Global |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Car parts | 1.271 | 1.403 | 0.752 | 0.747 |

| Covid deaths | 9.354 | 9.200 | 5.601 | 5.974 |

| Electricity hourly | 1.881 | 1.883 | 1.880 | 2.012 |

| Electricity weekly | 1.049 | 1.096 | 0.780 | 0.827 |

| Traffic hourly | 0.965 | 0.968 | 0.923 | 0.918 |

| Traffic weekly | 1.454 | 1.487 | 1.096 | 1.130 |

Table 2 MASE for each configuration tested. The best error is shown in bold

Now I think these results are very interesting. Firstly note how similar the results are between Local and Individual which I think gives some credence to my claim that the Individual configuration is essentially a local model. Secondly and more surprisingly there also seems to be a similar relationship in performance between the Multivariate and the Global configurations. For example the two best performing configurations for Car parts are Multivariate and Global both with a MASE of ~0.75 and Local and Individual have similar errors of ~1.3 and ~1.4 respectively.

Discussion

Now just a reminder here, that this Global setting is not something that has even been discussed in the paper, so I don't think this is a configuration that the authors have even considered. Nevertheless the Global and Multivariate configurations both seem to be on a par with each other (at least on these datasets). So what could be going on here? The common link between the Global and Multivariate configurations is that they are both trained on multiple datasets in a single model where the weights are shared. Clearly the characteristics of some datasets (ie Car Parts, Covid, Electricity Weekly and Traffic Weekly) lend themselves to the transfer of information between time series, but it challenges the notion that the only way (or maybe best way) to exploit the relationships between time series is to use a multivariate model. These results seem to suggest some evidence that for these Linear models information can be shared using univariate or multivariate methods to a similar effect. In fact given that Global univariate models are generally more scalable (due to them having fewer parameters) and don't require a dataset where all the time series share a common time span, and where the input always has to contain all the time series in the dataset I think the case for just using a global model is quite compelling. And if you're thinking well it's just specific to DLinear, well the NLinear model shows a similar pattern of behaviour. Now whether this holds for the long forecast horizon that these models were designed for is another question, but I think it's worth exploring further.